Most of North St. Louis County is part of what is formally designated as St. Ferdinand Township – and this fact alone is evidence of how the names of places and how we refer to them evolve over time. It is further complicated by the fact that the nearby city of St. Louis was founded by French traders in 1764, but it was on land that had been ceded to the Spanish the year before. The township has always been a somewhat confusing mélange of cultural place names deriving from both Spanish and French heritage. The western portion includes a grid of rues, while the eastern portion is known as Spanish Lake. The original French settlers referred to the area as “Fleurissant” which means flowering, but the first settlement included a Catholic shrine to the Spanish king St. Ferdinand, which meant that the city at the center of the township was originally named for him.

The fertile farmland of this area, at the confluence of the two largest rivers on the continent, led to significant growth of the population, and a greater need for schools to teach all of those children. In rural areas especially, this need has been historically filled by the one-room schoolhouse and that was true for well over a century of American history. One-room schoolhouses in America haven’t yet gone extinct, but there were once 190,000 of them scattered across all 50 states, and a 2005 survey showed only a few hundred left. So we are definitely living in the twilight of this educational archetype.

But let’s talk about the time period when this was the predominant method of educating our youth. Where did those schools come from? Who built them? Remember this was an age before the U.S. Department of Education and before the widespread movement to establish public schooling. The pattern that was followed and successfully replicated in rural communities across the nation was a group of parents who lived in close proximity to one another would come together, form an ad-hoc “school board,” elect officers of that board, and then decide how and where to build a school. Often, a board member would donate an acre of their farmland on which to build it. Others would donate funds to hire a teacher, and still others would offer up room and board for that teacher, so that they could be enticed to relocate and become a permanent member of the community. As the population grew, the original one-room schoolhouse might be replaced by a two-room, or three-room structure, single schools might be replaced by entire districts of schools, and of course the number of teachers also increased.

According to the History of the Hazelwood School District (Franzwa, 1977), there were 13 separate school districts in St. Ferdinand Township when they all eventually voted to merge into Hazelwood during the 1950s. In Chapter 7, the Twillman School is documented and recounts the involvement of our ancestor John Henry Twillman. But if you lived just a bit further east you attended the Prigge School (what is today known as Larimore School), named for our ancestor Charles F. Prigge. As the book states in Chapter 6, “Prigge is the predecessor name for the Larimore district, which elected to join the growing Hazelwood School District in a special election on July 29, 1951.” The book goes on to highlight that there were at least three schoolhouses with the Prigge name annotated on a 1927 map of the district. Only one of these sites is on property owned by Charles Prigge, so he must have been financially involved with the other two in some way. There is also mention of a “colored school” that may have been located on his property. Although there are no records of its exact location, the book contains a receipt for supplies to outfit the school, and speculates that “it is possible that Charles F. Prigge, who owned the land at that time, simply erected a building for children of his slaves.” Ignoring the fact that this would be in violation of the 1847 Missouri law that forbid the education of black people, the author offers no evidence of this claim, and it is also highly unlikely that Prigge was a slaveholder, given his membership in the Republican party.

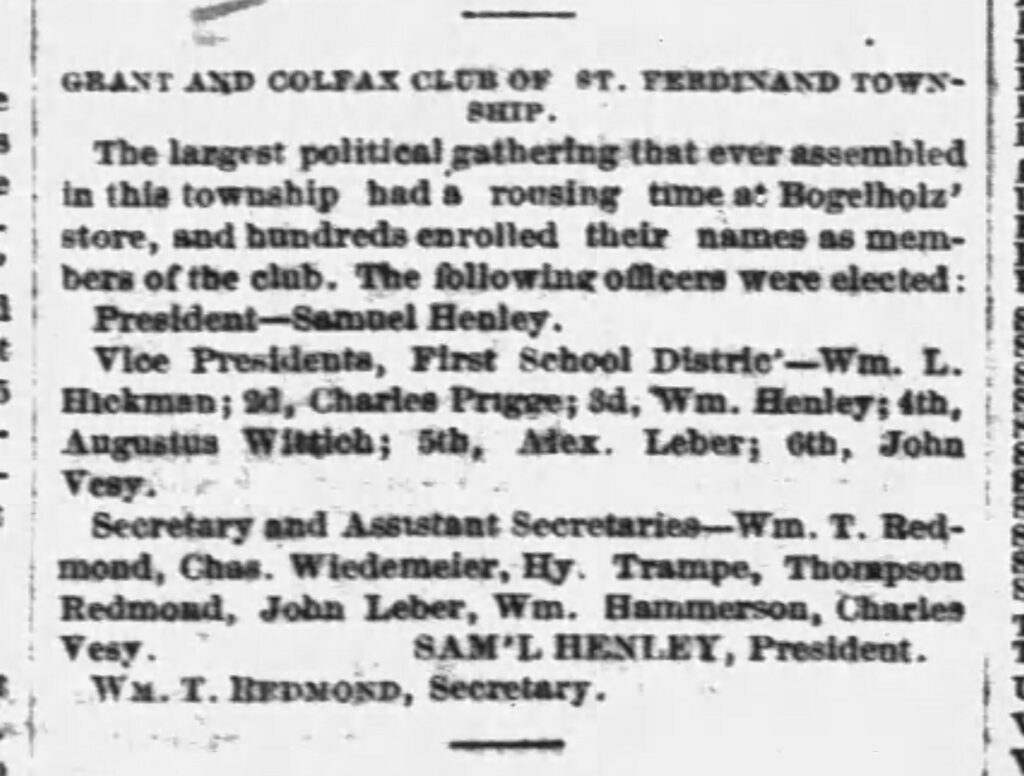

In 1868, he was elected vice president of the local Grant and Colfax Club. These clubs sprung up across the country during the campaign of President Ulysses S. Grant and Vice-President Schuyler Colfax to provide support for their election. Colfax was a founder of the Republican party and a staunch abolitionist. It is doubtful that a slaveholder would become a fervent supporter of his. What is perhaps more likely is that Charles Prigge’s convictions led him to help educate all of the children of his district, regardless of their race.

Charles Prigge died in 1883, but he demonstrated a strong sense of civic duty, serving as both an election judge and a school board member. His daughter Frances would go on to marry John Henry Twillman’s son Frederick in 1876, forever joining these two families whose lives were already intertwined in St. Ferdinand Township. Charles and his wife Christina are buried at Salem Cemetery in North County.

Pingback: This Old Road House – The Pipes Family Foundation