Between 1818 and 1836, Congress passed a series of laws providing pensions to soldiers of the Revolutionary War, many of whom were in poor health and destitute. These veterans had served their country, but their country had not shown them much gratitude. Our own ancestor, Captain John Pipes Jr., who served in the New Jersey line of the Continental Army, was eligible for the first of these pensions, but he died in 1821 at the age of 82. When the final Pension Act of 1836 was passed, his widow, Mary Morris Pipes, became eligible to collect. She was 77 years old at the time she submitted her application, and she passed away just a few years later in 1841. But this story isn’t about her – it’s about a piece of paper. A piece of paper that is approaching 250 years of age, and might be one of the most well-traveled pieces of paper in American history.

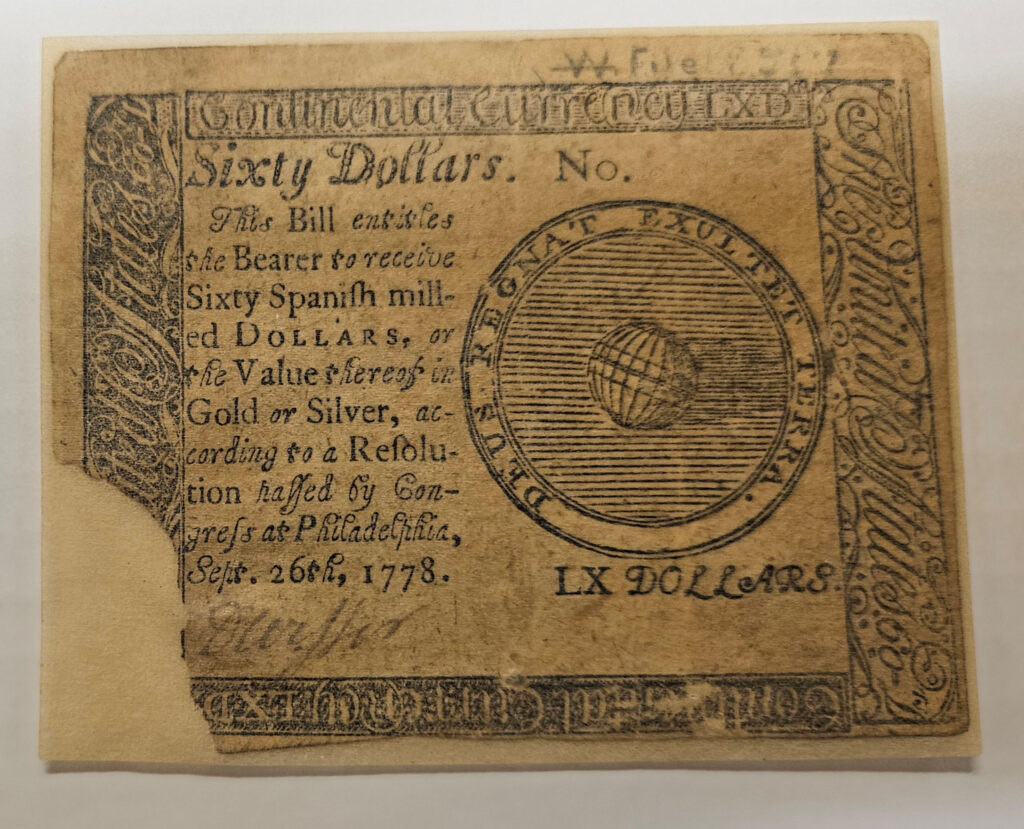

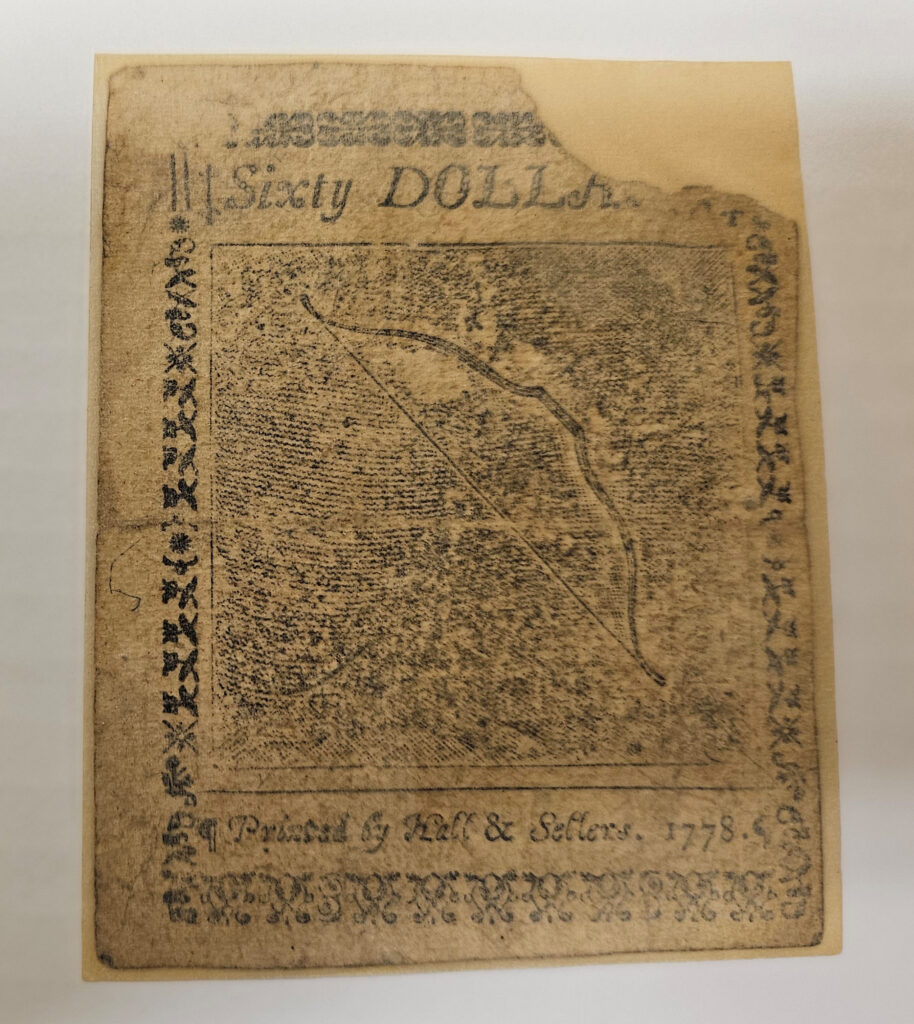

You see, Mary Morris Pipes had great difficulty applying for her pension benefits because she was missing a different but very important piece of paper: her husband’s discharge from the Army in 1780. This document was the only proof that a soldier had served, listing when and where, and who their commanding officers had been. Mary’s husband had either never received a discharge document, or he had lost it in the intervening 40 years between his discharge and his death, which is not at all surprising. But Mary needed that document. Moreover, she needed proof that she was in fact married to John Pipes. Additionally, she needed proof that their marriage had occurred prior to the end of the War in 1783. That is a lot of documentation for a woman in her 70s to lay her hands on. We have to respect Mary’s grit and determination, because much of her 69-page pension file at the National Archives details her efforts to prove these aspects of her relationship to John. But she still didn’t have John’s discharge papers.What she did have was the star of our story: a $60 note of Continental currency, printed on Sep 26th, 1778 by the Philadelphia print shop of Hall & Sellers. John Pipes had received this note as partial payment of his officer salary, and as it said right on the note:

This Bill entitles the Bearer to receive Sixty Spanish milled Dollars, or the Value thereof in Gold or Silver

Spanish Milled Dollars, also known as “pieces of eight,” were literally the coin of the realm from the time the Spanish landed in North America in 1565 right up until the Civil War. They were the standard currency, and the most trusted. But they were also very hard to come by at the end of the Revolution, and many soldiers propagated the oft-used phrase that something wasn’t “worth a Continental” because they were left at the end of their service with these worthless pieces of paper. John Pipes held onto that Continental note for the rest of his life, perhaps hoping that one day the US government would honor their commitment to him. But they didn’t, and Mary still had that note when she submitted her application, so she included it with the rest of her paperwork in the hopes that it would offer proof that her husband had indeed been one of the many thousands of soldiers who were never properly compensated.

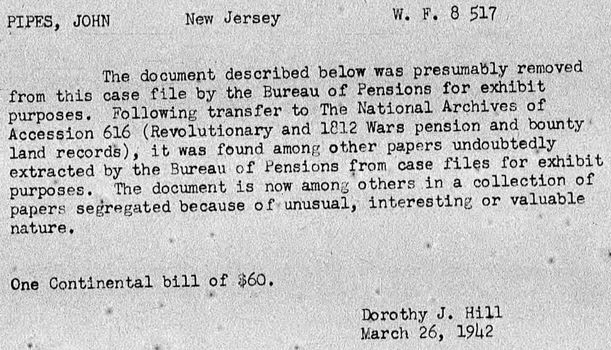

Thus, the journey of this $60 note continued, from its origin in Philadelphia, to its payment on a battlefield in New Jersey, to its long-term storage in a box or a drawer in Kentucky, where Mary Morris Pipes was living when she mailed her application to the War Department in Washington, D.C. The note lived in a forgotten folder at the War Department for decades until it was transferred to the Bureau of Pensions at the Department of the Interior in 1849. In April 1904, this note made a brief appearance at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (aka the World’s Fair) in St. Louis as part of the Pension Bureau’s exhibit there (according to page 16 of Mary’s pension file). It then returned to a dusty drawer in Washington until 1930 when the Pension Bureau moved again to the newly established Veteran’s Administration. The note is referenced once again in 1942 as being segregated from other records because of its “unusual, interesting, or valuable nature.”

Then in 1961, a descendant named Charles Pipes, who was then serving as Treasurer of the Kentucky chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution, read John Pipes’s pension file and wrote to his U.S. Senator inquiring about the $60 note that had at one time belonged to his family. Charles Pipes wanted to know if the note could be temporarily put on display at the Kentucky Historical Society. This set off a chain of events, and a flurry of correspondence (most of which is captured in the pension file), ultimately resulting in the Veterans Administration agreeing to loan the note to them. According to a story in the Advocate-Messenger in Danville, Kentucky, the note apparently went missing at some point after 1961, and was not recovered until 2017, at which point the National Archives asked for the note to be returned.

A few weeks ago, this author inquired about the note and asked if there were images of it available. The National Archives responded with the two photos below of the actual note that used to belong to Mary Morris Pipes. The Pipes Family Foundation is proud to offer this account and these pictures to any other descendants of John Pipes Jr. who might be interested in this unusual and compelling bit of family history.

Pingback: Veteran of the Revolution – The Pipes Family Foundation

Very interesting. Great work on the research.